By the year 2020, cardiovascular disease (CVD) will be the leading cause of death worldwide. CVD is increasing for many reasons, including longer life spans, increased tobacco use, and the effects of increased urbanization—decreased physical activity, increased fat consumption, and increased psychosocial stress. These factors lead to increased obesity, resulting in increased rates of dyslipidemia, dysglycemia, and hypertension. Dr. Salim Yusuf, McMaster University and Hamilton Health Sciences Corporation, Canada, discussed the increasing burden of CVD throughout the world and described studies on CVD risk factors.

The percentage of people living in urban settings increased from 36.6% in 1970 to 44.8% in 1994, and is expected to increase to 61.1% in 2025, worldwide. In early industrialized regions such as North America and Europe, age-related heart disease mortality peaked in 1950 and has declined by about 50% since then. In late industrialized countries such as India and China, CVD mortality will peak in about 2020.

The Interheart study evaluated data from 28,000 cases of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and controls from 52 countries. Nine risk factors accounted for 90% of AMIs in the overall study population: abnormal lipid levels, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, abdominal obesity, psychosocial factors, and lack of fruits and vegetables, exercise, and moderate alcohol consumption. In urban societies, 99% of cases in the control group had at least one risk factor for CVD.

|

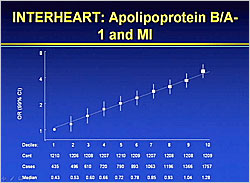

Figure 1. Interheart: Apolipoprotein B/A-1 and MI

【Click to enlarge】 |

|

|

The Interheart study showed that for every 10% increase in apolipoprotein B/A-1 levels, there is a corresponding increase in MI risk (Figure 1). CVD risk also increases with increased daily smoking; every cigarette per day increases risk by 6%. Importantly, this study showed that all the identified risk factors had the same impact in each of the regions studied.

The Interheart results led to a conceptual model of factors that influence an individual’s health—genetics, habits and lifestyles, society, community and family, and lifetime exposures. According to Dr. Yusuf, the risk factors for CVD are set by 6 months of age. He is currently conducting a study following 1,000 families for 10 years to analyze day of birth risk factors.

Data from the seven countries study from 1950 showed a 40-fold variation in CVD in males in different countries, a 30% variation within the same country, and similar variations within regions. These differences are not due to genetic variation but can be explained by government policies, group exposure (e.g. air, water, soil), built environment, socio-cultural factors, advertising, costs, bio-environment, and quality of and access to healthcare.

|

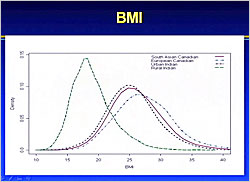

Figure 2. PURE Study: BMI

【Click to enlarge】 |

|

|

The Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiologic (PURE) Study is analyzing these factors in 140,000 subjects from 18 countries from every continent worldwide, including 90,000 from Asia. Results will be available in November 2009. Data from the PURE pilot study comparing body mass index (BMI) of people living in rural India, urban India, and Europeans and South Asians in urban Canada show a big difference between those living in rural India and those living in urban areas (Figure 2). BMI also is highest in high income countries but is increasing in low and middle income countries. The results also show that BMI has increased since 1950. For example, the BMI of Japanese has increased from 18 to 26, heralding a future epidemic of CVD in Japan. Similar differences in LDL levels and systolic blood pressure (SBP) were observed between rural and urban populations. Urban versus rural areas had significantly higher rates of diabetes (19.3% vs. 1.8%), hypertension (29.7% vs. 9.2%), and coronary heart disease (8.6% vs. 4.7%) (p<0.001).

A goal of the PURE study is to understand why there are differences in risk factors between different regions. For example, smoking rates are about 40% in Chile and Argentina versus 10% in Iran and the United Arab Emirates. A comparison of cigarette costs and smoking rates in several European countries shows that lower cost correlates with higher smoking rates in men but not in women. Understanding the reasons for this is a key factor in reducing CVD.

Dr. Yusuf calls built and nutrition environments that promote obesity “obesogenic environments.” Built environments that promote physical activity, such as walking, are associated with lower obesity levels than those that do not. The nutrition environment, comprising food policy, social norms, and access/exposure to healthy/unhealthy foods, affects obesity rates in a community.

CVD death rates in males dramatically decreased from 1950 to the 1990s in Finland and the UK, but markedly increased in Poland until 1990 and then suddenly decreased. A similar pattern occurred with cancer rates. The explanation is that government subsidies for animal products ended with the fall of the communist government in Poland, causing a marked increase in fruit and vegetable consumption and decreased animal fat consumption.

Modifying 3 risk factors would prevent most MIs in North America—reducing smoking from lifelong to none reduces risk by 2/3; decreasing SBP by 20 mmHg reduces risk by 1/2; and lowering LDL by 1 mmol/L cuts risk by 1/3, for a theoretical cumulative reduction of about 5/6.

|

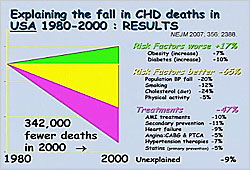

Figure 3. Explaining the Fall in CHD Deaths in the USA 1980-2000

【Click to enlarge】 |

|

|

There was a 50% decline in age-adjusted CHD mortality rates in the US from 1980 to 2000. Although obesity and diabetes increased (CHD mortality +17%), other risk factors decreased (CHD mortality -65%), and treatments improved (CHD mortality -47%), explaining 90% of the 50% reduction in CHD mortality (Figure 3). The same pattern has been observed in several other countries.

Dr. Yusuf concluded that millions of lives can be saved through better treatments for CVD. Improving adoption of evidence based practices and improving access to care for disadvantaged populations could substantially prevent many premature deaths in developed and developing countries. Systems and incentives are needed to implement simple but effective therapies such as statins and blood pressure control.

Additionally, it is important to understand and modify risk factors by developing policies to reduce smoking, increase physical activity, and promote healthy eating. This will entail a life course approach to CVD prevention by implementing what we know and making prevention more accessible. If such measures are implemented, large reductions in CVD are possible in the next two decades.

|